CRB Response

A grant-funded organization managed through the University of Hawai‘i that provides education, awareness, detection, prevention and treatments to protect Hawai‘i from the threats and impacts of CRB.

Mālama Learning Center

A nonprofit that designs hands-on, place-based programs that teach sustainable, culturally grounded living. It has programs around youth, teachers, community members, site restoration and wildfire prevention.

Big Island Invasive Species Committee

A project of the University of Hawaiʻi- Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, BIISC aims to prevent, detect and control the establishment and spread of invasive species on Hawai‘i Island.

Community Coconut Program

Housed under the state Kaulunani Urban & Community Forestry Program, the Community Coconut Program is dedicated to fostering “niu as a relationship rooted in community and aloha ‘āina.” This vision began with Niu Now, a community grass-roots movement committed to the coconut and to planting uluniu (coconut groves) since 2018.

Niu Now

A community cultural agroforestry movement working to affirm the importance of niu, coconut and uluniu. At the center of its movement is the re-establishment of a loving relationship with niu and the ancient knowledge practices of Hawai‘i’s coconut heritage as a “tree of life,” a complete food system. The movement is led by Dr. Manulani Aluli Meyer and Indrajit Gunasekara.

“Aloha niu. ‘A‘ole coconut rhinoceros beetle.” “Mālama i nā kumu lā‘au niu.” “Kōkua i ka niu.” “I love coconuts.”

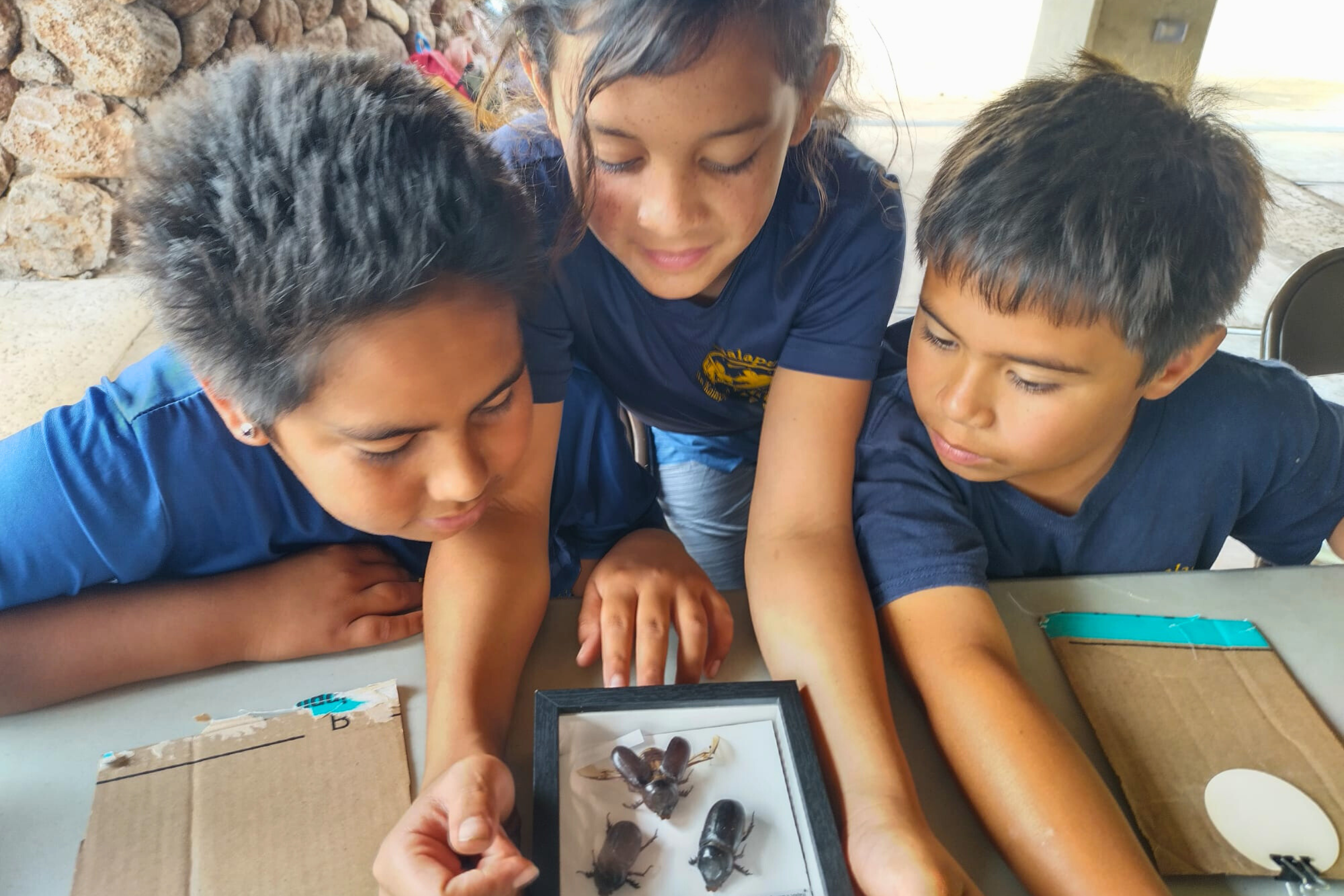

These short phrases are meant to have a rippling impact thanks to the 80 Moloka‘i fourth graders who created colorful campaign buttons to help raise awareness about the Coconut Rhinoceros Beetle (CRB) at their Keiki Earth Day event in April.

“The idea was they would show their parents or other people the buttons and then spark a discussion from there,” said Pauline Sato, co-founder and executive director of Mālama Learning Center, a nonprofit that provides ‘āina-based education.

The Moloka‘i community is on high alert, she said, given the beetle’s impacts on the other islands.

Native to Southeast Asia, CRB is an invasive pest in the Pacific and has been in Hawai‘i since 2013. The destructive beetles are present throughout O‘ahu and in parts of Kaua‘i and Hawai‘i Island. Maui only had one detection so far, and Lāna‘i and Moloka‘i haven’t had any.

The beetles target palm trees, using their horns and front legs to bore into the crowns so they can eat developing leaves and sap in the inner core. If the beetles do enough damage, they can severely weaken and kill the trees.

Community members are particularly concerned about their impacts on the endemic loulu palm and niu (coconut trees). Niu were introduced to the islands by early Polynesian voyagers and are important sources of food and cultural practices.

With plenty of palm trees, moisture and green waste that provides ideal breeding sites, Hawai‘i’s environment is particularly favorable to CRB. Yet insufficient funding and staffing have complicated Hawai‘i’s ability to stop it.

Officials are looking to a biocontrol solution that has been used to reduce CRB populations in other countries, but it’ll still be a couple years before it can be used locally.

In the meantime, officials urge community members statewide to stay informed, inspect high-risk material for signs of the beetle and properly manage their green waste. They’re also working to define government agency response roles and better coordinate on major invasive pest efforts.

Unfortunately, now people are paying attention because it’s in their backyard, but we really wanted people to pay attention before it got to their backyard. … We don’t really think it’s a serious problem until it’s in front of our face, and then we’re like, ‘how come no one did anything?’ And it’s like, no, we were trying. We were trying to tell you guys, but it’s just the sense of urgency wasn’t there because people couldn’t see it.

Mālama Learning Center educated Moloka‘i fourth graders about CRB during a Keiki Earth Day Event in April. The students created campaign buttons to help raise awareness about this destructive beetle. | Courtesy: Pauline Sato of Mālama Learning Center

Capacity for Impact

Keith Weiser, deputy incident commander of the CRB Response, said there were few options to treat infested palms and green waste when the beetle was first found at Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam. Created in 2014, CRB Response is one of the main entities that has been responding to CRB.

Initial responses focused on intense surveying, deploying more detection traps, green waste management, community education, and researching effective treatments and management strategies.

Weiser said a major lesson learned from responding to the base’s infestation was that green waste management was effective. A female beetle can lay up to 140 eggs during her lifetime, and larvae spend about 5.5 months living in decaying material, so the base created a strict policy requiring green waste to immediately be burned or chipped and then removed from the premises.

The military’s top-down structure meant that everyone on base followed the policy, he said. But that’s hard to achieve in a regular neighborhood or other geographic area. To be effective, treatments and management strategies need to be implemented at a landscape level.

CRB will fly up to two miles a day when looking for food sources, but experts said that their rapid spread on O‘ahu over subsequent years was caused by movement of contaminated materials. Beginning in 2022, the Hawai‘i Department of Agriculture (HDOA) established rules to restrict the movement of palms taller than four feet, plus compost and other landscaping materials, heading from O‘ahu to the neighbor islands.

Such materials can only be shipped if mitigative measures are taken, such as fumigating or heat-treating green waste or using chemical treatments on palms, said Jonathan Ho, manager of HDOA’s Plant Quarantine branch. The mitigative measures and treatments need to be witnessed by HDOA Plant Quarantine staff.

Hawai‘i Explores Natural Approaches to Address Coconut Rhinoceros Beetle

Body Copy Text LinkEvery Friday afternoon, O‘ahu farmer Daniel Anthony of Hui Aloha ‘Āina Momona can be found climbing coconut trees around the Ko‘olau Range, removing old leaves and tending to green waste. He then sprays the trees with a series of nutrient-rich...

Nonetheless, the rapid spread on O‘ahu and insufficient funding led the state in 2023 to officially move away from eradication on the island and instead focus on long-term management to reduce beetle populations, minimize damage and prevent the beetle from spreading to the other islands.

Then, detections occurred on Kaua‘i in May 2023, on Hawai‘i Island in October 2023 and on Maui in November 2023.

CRB Response is predominantly funded to manage populations near airports and ports on O‘ahu and around high-risk material being shipped to other islands, and HDOA’s response capacity has been limited by understaffing. Its Plant Quarantine branch, for example, which is the state’s “first line of defense” in keeping pests out of the islands and regulates inter-island movements of plant materials, only has two staff members on Kaua‘i, 13 on Maui and 13 on Hawai‘i Island, Ho said.

“When you look at the amount of staff that the department has who do this work, there’s not enough people and resources to do it,” he said.

HDOA and CRB Response collaborate with the Invasive Species Committees, county governments and other state agencies to pool resources, but with limited funding, they’ve had to be strategic about where they put their time and effort.

Land ownership, whether they can get authorization to do surveys and eradication on private property, and available tools factor into those decisions. HDOA received a permit from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to use a pesticide called Demon Max on coconuts and palms in 2023, but it was not authorized for use on O‘ahu, HDOA wrote in an email. Demon Max was applied via drone on Kaua‘i in September and October 2023, months after the original detection. Part of the delay was waiting on the EPA’s approval.

Drones also can’t be used near military bases or airports, limiting where this tool can be used, Weiser said.

“More palms is harder, more green waste makes it harder, more different landowners makes it harder—all those things go into a determination of how much resource is possible to actually get a chance to eradicate or at least delay the spread of the populations from that area,” he said.

A larvae found by a farmer’s dog in a green waste pile on Kaua‘i. Larvae spent about 5.5 months living in and eating decaying material. | Noelle Fujii-Oride, Overstory

More palms is harder, more green waste makes it harder, more different landowners makes it harder. So all those things go into a determination of how much resource is possible to actually get a chance to eradicate or at least delay the spread of the populations from that area

Emergency Response for New Finds

The Big Island Invasive Species Committee (BIISC) knew it was inevitable the beetle would make its way to Hawai‘i Island, so as soon as CRB was found on Kaua‘i, it contracted with a local detection dog company to begin training a dog, named Manu, to find CRB larvae, said Franny Brewer, BIISC’s program manager.

Manu was still in training when the first detection occurred in Waikoloa Village. BIISC increased its surveying and trapping efforts, and HDOA treated palms around the detection site. No beetles have been found in the Village since September 2024.

That’s another lesson learned from O‘ahu, Weiser said—to “go all in” while the beetle population is still small and confined to a limited area. That’s meant increasing surveying and early detection efforts and then treating new areas where CRB are discovered.

“Throw everything at it, and if you eradicate it, great,” he said. “And then if you don’t eradicate it, then go into management mode or containment mode.”

Such early intervention efforts also worked on Maui, where no CRB have been confirmed since the original detection of 17 live larvae in Kīhei in November 2023.

Kaua‘i is an example where the focus shifted to containment due to the beetle quickly establishing itself in three distinct areas. Limited resources and understaffing, combined with the beetle being detected on Maui and Hawai‘i Island, also hindered eradication efforts.

But now the beetle is present in Kona. Brewer said she theorizes that the Kona detection is separate from Waikoloa because all the Kona findings have been at or around the airport. Nonetheless, she said Hawai‘i Island has benefited from seeing what has and hasn’t worked in the state’s response over the past 10 years.

“Sometimes the thing is that you have a product that could work, but it’s never been applied to palm trees in the United States, so it’s not on the label,” she said. Removing the red tape can take years and interrupt invasive species responses. “It’s been really great that that was all in place by the time we got these beetles.”

HDOA said it has treated 1,322 palm trees on the west side of Hawai‘i Island.

“It’s all hands on deck right now for Kona,” Ho said.

Last month, the County of Hawai‘i awarded BIISC a $250,000 grant to do more backyard surveys, trapping, outreach and education around the CRB. That grant will also support its other invasive species work, though Brewer said it’s the first time BIISC is being funded specifically to combat CRB.

She added that BIISC has received “amazing” response from the West Hawai‘i community in helping to eradicate CRB. Many Waikoloa residents, for example, hosted detection traps in their backyards and allowed surveys on their properties.

And BIISC continues to have a robust community trapping network within the detection zones and across the island. That trapping network enables BIISC to have a critical early warning system so it can respond when the beetles show up.

“There’s just not enough of us and not enough funding for us to do this all by ourselves,” she said.

The Big Island Invasive Species Committee and Hawai‘i Department of Agriculture have been conducting site surveys in Kona to try and find breeding sites. | Courtesy: Big Island Invasive Species Committee

‘Now People are Paying Attention’

Based in Pālehua, Mālama Learning Center has been helping raise awareness about CRB in West O‘ahu schools and the broader community for 10 years.

Staff presented to classes and engaged students in digging through mulch in their school garden to check for CRB breeding sites, participating in broader community outreach events, collecting data about CRB on their campuses and in their communities, and other activities.

The nonprofit even created a Backyard Beetle Watch program—complete with t-shirts and visors—to encourage community members to be on the lookout for CRB in their neighborhoods. But community members got bored when they didn’t see signs of the beetle.

With CRB damage now commonly seen throughout West O‘ahu, community members are staying aware of the beetle, Sato said.

“Unfortunately, now people are paying attention because it’s in their backyard, but we really wanted people to pay attention before it got to their backyard,” she said. “I think that’s just human nature. We don’t really think it’s a serious problem until it’s in front of our face, and then we’re like, ‘how come no one did anything?’ And it’s like, no, we were trying. We were trying to tell you guys, but it’s just the sense of urgency wasn’t there because people couldn’t see it.”

CRB damage has been especially prevalent along parts the Leeward Coast and North Shore, where the Honolulu Department of Parks & Recreation (DPR) has removed nearly 200 dying or dead trees; they’ll be replaced with shade trees not susceptible to CRB.

Separately, the Community Coconut Program under the state’s Kaulunani Urban and Community Forestry Program found that 60% of the 1,200 palm trees it surveyed between Nānākuli and Ka‘ena had some level of CRB damage.

Now the beetle is starting to cause damage in urban Honolulu, an area where it hasn’t been seen for 10 years. Earlier this month, Honolulu’s Division of Urban Forestry started injecting palms at Kaka‘ako Waterfront Park with a preventative treatment, called Xytect. Four other parks from Kaka‘ako through Ala Moana will be treated, too. The division already treated palms at Hanauma Bay Nature Preserve and at parks around Lē‘ahi.

The intent is to create a protective barrier in the urban core, where the City has about 4,000 palm trees, said Roxanne Adams, lead arborist and the head of the City’s Division of Urban Forestry. She added that mitigating the spread of CRB is more difficult outside the urban core due to the number of private landowners, as well as the presence of agricultural activities and breeding site debris.

“While we would like to treat as many palms as possible, that cost of labor that goes into it … and the fact that we have to do the treatments on a regular basis, almost an annual basis, makes it very difficult to do this type of treatment,” she said.

The treatment is being provided by HDOA, and a four-person crew will be injecting palms year-round. Adams said coconuts are already removed from trees in parks to prevent them from falling on park patrons. Flowers are also being removed to protect pollinators.

She added that her division hopes to treat bigger groves on the other side of the island, but she doesn’t know if they’ll be able to get the resources to do it. In the meantime, her division has changed its green waste practices to chip waste straight away and then cover with netting. It is also no longer using mulch.

Honolulu’s Division of Urban Forestry began injecting trees at Kaka‘ako Waterfront Park with an insecticide called Xytect, the beginning of a several months-long process to create a protective barrier from Kaka‘ako throuth Ala Moana. | Noelle Fujii-Oride, Overstory

‘We Still Have to Plant Them’

Mālama Learning Center hopes to help the West O‘ahu community realize that they can help Hawai‘i control CRB through the choices they make.

“We got to take the responsibility in our own hands,” she said. “If we are the ones moving them around, we have to make sure we’re the ones (being) careful and keeping our communities safe.”

The nonprofit is one of seven local organizations funded by a HDOA grant for community-based CRB management on O‘ahu. Other grantees’ projects include creating an ahupua‘a management model in Kahalu‘u; a beetle collection competition and installing a thermophilic, aerobic composting machine on the North Shore; and education and outreach around the island.

Mālama Learning Center plans to bring schools and community members to its Awawalei food forest in Kunia at the Hawaiʻi Agriculture Research Center to demonstrate proper green waste management, how to wrap palm trees with netting and how to cultivate niu. Sato said cultivating niu is especiallly important.

“It’s almost like people feel like there’s nothing they can do other than poison their trees, and we’re hoping that will change, that there will be a different kind of solution coming up, but we still have to plant them,” she said. “We still have to grow them, otherwise they will disappear.”

Separate from the HDOA grant, Mālama Learning Center is also working with Moloka‘i community members to plant niu and save certain varieties specific to the island.

It’s one of several efforts to cultivate niu. The Community Coconut Program and a grassroots movement called Niu Now work together and with others to care for 16 niu nurseries on O‘ahu, Hawai‘i Island and Maui. They follow the ancient practice of caring for uluniu (coconut groves), which focus on growing niu for food, cultural practices, musical instruments, and spiritual and ecological needs.

The two groups seek to affirm the cultural, nutritional and ecological importance of niu and uluniu, as well as safeguard the genetic diversity of Hawai‘i’s coconuts. Indrajit Gunasekara, director of the Community Coconut Program and a co-founder of Niu Now, said the groups have tracked over 100 coconut varieties, with a particular focus on those that existed in Hawai‘i prior to European contact.

In times of old, coconut trees were often planted for the benefit of future generations, said Kehau Kahele-Madali, program assistant with the Community Coconut Program.

“Your grandparents, your great grandparents, could have planted that tree and you see it today, yeah?” Kahele-Madali said. “And it just goes to show that spiritual connection to not only the niu itself, but through your own moʻokūʻauhau and that tree’s moʻokūʻauhau—you know, their family lineage and your family lineage. And just bringing both those aspects together is super, super important, and reclaiming our identity as kānaka.”

Gunasekara said that CRB wasn’t a visible issue when Niu Now and the Community Coconut Program were created. They only started seeing its impacts around 2021; since then, they’ve been wrapping their young trees with Tekken netting and flooding their mulch. They also helped plant and replace niu at Keoneʻōʻio (Tracks Beach Park) earlier this year.

He and Jesse Mikasobe-Kealiinohomoku, who volunteers with Niu Now, said responding to CRB needs a more holistic approach than just treating trees with chemicals, which could harm the trees and surrounding ‘āina.

“When the issue is affecting everybody, a community, that individual perspective, individual thinking, has very little value or no value,” Gunasekara said. “In the first place, the coconut is not somebody’s private property. It’s indigenous to this place, to the community. That tree belongs to the root culture here.”

Kehau Kahele-Madali, Indrajit Gunasekara and Jesse Mikasobe-Kealiinohomoku are working to safeguard niu genetic diversity and cultivate niu on O‘ahu, Maui and Hawai‘i Island. One of the uluniu they care for is at UH West O‘ahu. | Noelle Fujii-Oride, Overstory

The Fight Ahead

At the end of May, Hawai‘i got the green light to import the Oryctes rhinoceros nudivirus, which has been used to reduce CRB populations in other counties.

Weiser said research will now need to be done to study the safety and efficacy of the virus, ensuring it will affect the type of CRB Hawai‘i has and that it won’t harm any other species important to the islands, like Kaua‘i’s endemic scarab beetle.

Meanwhile, HDOA has been increasing its staffing thanks to a record infusion of funding from the state Legislature last year for biosecurity measures and invasive species programs. Ho said one of the legislative measures, Act 231, led to 44 new positions, though the department is still working on filling them.

Act 231 also designated HDOA as the lead agency for the state’s biosecurity efforts. The department is expected to receive about $12 million for biosecurity efforts from the state Legislature this year, Ho said.

“It’s never fast enough unfortunately as it relates to the damage,” Ho said. “Everyone can see the damage that’s happening with CRB, and the department is kind of playing catchup, and the fact that the Legislature provided us with the money last year and provided more funds this year, I think, will give us the opportunity to kind of turn the tide on the problem.”

Weiser said UH, HDOA and DLNR are also working on a memorandum of understanding to define roles, improve coordination for invasive species responses, and create invasive species plans for each county.

That work will detail things like which actions are appropriate to be taken in areas deemed for eradication versus containment and who will be gaining access to properties for field surveys.

Weiser added that, while biocontrol will help reduce beetle populations, it still probably won’t lead to the eradication of CRB on O‘ahu.

“You can’t get rid of all the decaying plant material on O‘ahu with, even with things like pesticides,” he said. “You can’t apply enough pesticides concurrently across the whole island to kill all them, and even if you did, that would be too ecologically impactful to probably be worth it.”

He said one idea is for thoroughly infested areas, like O‘ahu, to set up management zones. For example, areas dedicated to niu cultivation could have a one-mile buffer zone where advanced green waste management is required and trees along the perimeter are treated to act as a protective barrier. But at this point, creating those zones will depend on identifying whose mandate it falls under and bringing the right people to the table.

On Maui, Plant Quarantine branch inspectors conduct regular inspections of compost shipped from O‘ahu, as well as at Maui big-box stores that sell landscaping materials, HDOA wrote in an email. Its Plant Pest Control personnel are also starting a program to inject insecticides in palm trees that surround the ports of entry to add a protective barrier.

On Hawai‘i Island, Brewer said the next few months are critical for response efforts in Kona, where the presence of the agricultural park and nurseries provides more potential places for beetles to breed.

They expect to see fewer adult beetles over the next few months as that original Kona cohort dies off and more larvae develop, so the search is on for breeding sites.

“We’re a little bit concerned, but I still think, yes, that we have a chance at eradication,” she said.

How to Help Hawai‘i Contain the Coconut Rhinoceros Beetle

Getting this invasive pest under control requires community-wide involvement. Here’s a quick guide to help you be part of Hawai‘i’s response.