Awaiaulu

Shaping History: The Role of Newspapers in Hawaii

2008 article in The Hawaiian Journal of History

An essay written by Noenoe K. Silva that seeks to provide a fuller history of the characteristics and contents of the first four Hawaiian-language newspapers.

Editor’s Note: This article is the first in a series about the history of journalism in Hawai‘i and focuses on some of the earliest ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i newspapers published from the 1830s and 1850s. As a new local newsroom, we acknowledge that there are many others who came before us and that there are many lessons to be learned from their contributions. While it is Overstory’s policy to include Hawaiian diacritical marks, we omitted them when ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i newspaper titles did not use them.

You wouldn’t think that four 9-by-11-inch sheets of paper would have a significant impact, but in 1834, they signaled a new milestone for the Hawaiian Kingdom: Its first newspaper, Ka Lama Hawaii, was published in ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i by students at Lahainaluna Seminary.

The newspaper was the first to be printed west of the Rocky Mountains—and the beginning of a legacy of over 100 ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i newspapers to be published across Hawai‘i until the mid-20th century.

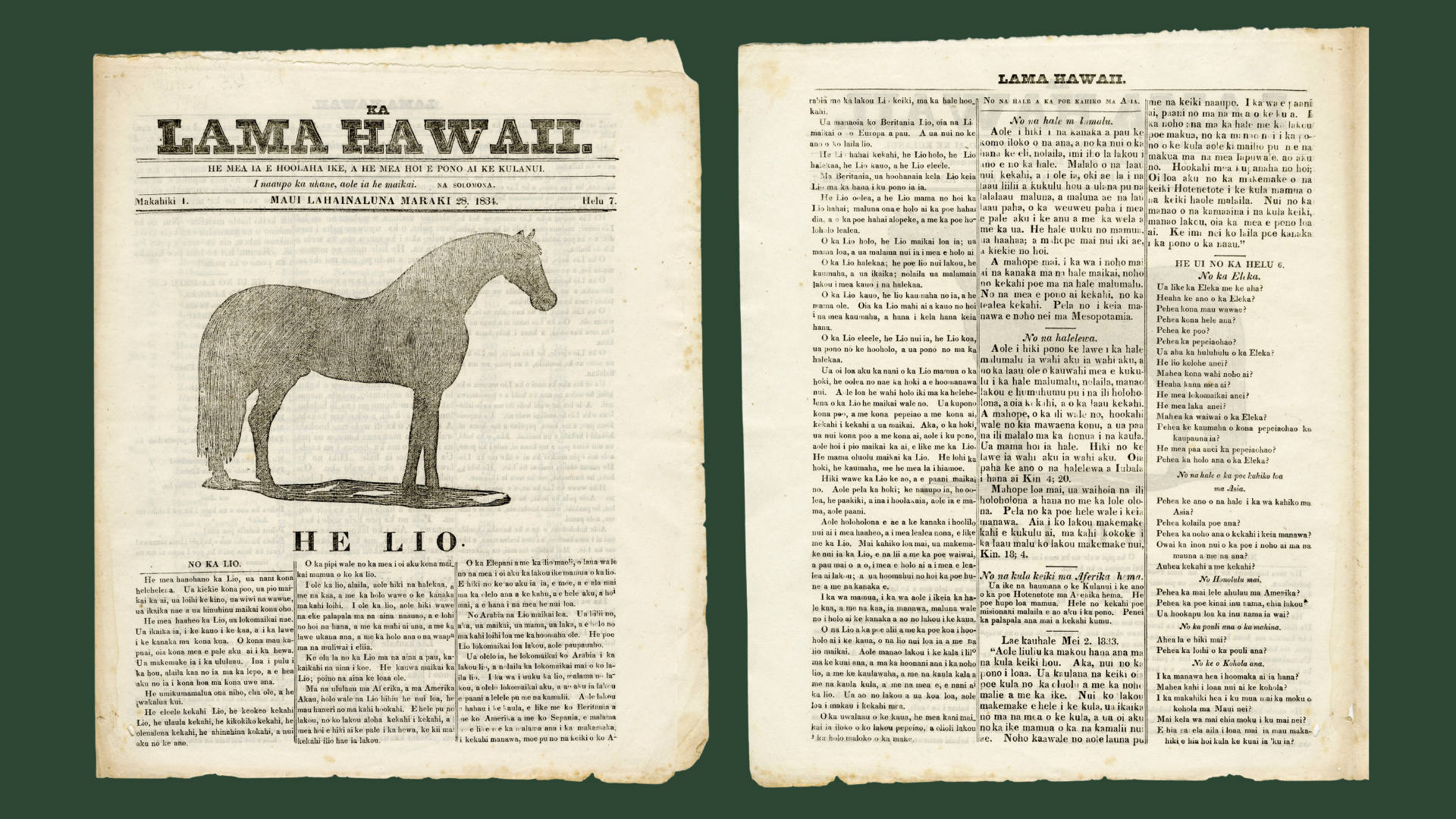

Much of the Hawaiian Kingdom was quickly embracing literacy, so the weekly Ka Lama was an educational tool. Its articles talked about Christianity; the Bible; and animals like elephants, giraffes, rhinos, hippos and buffalos. And although Ka Lama’s main audience was the Lahainaluna school community, the paper was shared widely throughout the Kingdom.

“Just imagine what this provided for Hawaiians who never left the island chain, hearing about it, seeing drawings and even stories about places and things that they never knew existed,” said Puakea Nogelmeier, executive director of Awaiaulu, a nonprofit that develops Hawaiian language resources.

He added that although Ka Lama and other early ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i newspapers were led by missionaries, they were not purely missionary products. They became a repository for Native Hawaiians to preserve oral traditions and exercise Indigenous thought and discourse as foreign diseases and abrupt lifestyle changes decimated the Hawaiian population. The papers also shared local government news and delivered information from around the world.

“The advent of literacy is huge because it allows the sort of the permanence of writing, but the newspapers as an acknowledged and collective repository is also really, really huge,” Nogelmeier said. A man named S. K. Kuapuʻu, for example, encouraged other Hawaiians to put their stories into writing “because a knowledgeable person dying was like a library burning down,” he added.

Over 100 ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i Newspapers

The ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i newspapers printed over 125,000 pages between 1834 and 1948. Microfilm copies are available for viewing through the Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ Papakilo Database.

Ka Lama Hawaii’s March 28, 1834 issue. | Digital reproduction courtesy of Bishop Museum Library and Archives.

Early Literacy in Hawai‘i

Native Hawaiians were quick to embrace literacy. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions arrived in 1820 and soon taught Hawaiian chiefs how to read and write in English. Less than two years later, they and the Hawaiian chiefs created the written form of ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i.

Nogelmeier said the chiefs immediately recognized that literacy could help the nation progress. He cited Queen Ka‘ahumanu, who was writing lengthy letters by June 1822.

“(In) Ka‘ahumanu’s very first letter, she says, ‘We want this literacy. It will make us wiser.’ It’s huge,” he said. “It’s a smoking gun because she becomes the driving force.”

Then, in 1825, 12-year-old King Kamehameha III ascended the throne and declared “mine will be a nation of literacy.” He requires all konohiki—managers of ahupua‘a land divisions—to provide land, labor and income for a school and teacher. That leads to the 1831 creation of Lahainaluna Seminary, a school for young men.

Nogelmeier said the Ka Lama was introduced not as journalism but as a teaching tool to enhance the knowledge of Lahainaluna’s teachers.

“We’re already 12 and 13 years into the literacy project, so this, although it’s created for the school, it becomes national immediately,” he said. “Everybody wants this.”

Kingdom newspapers referenced universal literacy around the 1840s.

“There’s lots of random references in the newspaper where they’ll say, ‘yeah, if someone couldn’t read or write, where would you find someone like that?’ So the national assumption of its own identity was as a literate nation,” he said.

While the common denominator of the early newspapers discussed here is the desire that their editors had to convert Hawaiians to a radically different system of beliefs and practices, the opening up of spaces for written expression, coupled with the Hawaiian embrace of reading and writing, made the newspapers a vital arena in which crucial questions about culture, knowledge, and politics could begin to be publicly debated.

Collective Conscious

A second ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i newspaper, called Ke Kumu Hawaii, began printing about nine months after Ka Lama. Ke Kumu was published out of the mission headquarters in Honolulu and targeted all mission schools and the public.

Helen Geracimos Chapin, author of the 1996 book “Shaping History: The Role of Newspapers in Hawaii,” wrote that the two papers marked the beginning of Hawai‘i’s establishment press, a category of newspapers that represented the Kingdom’s controlling interests. Their missionary editors ran articles that talked about the desirability of an American-style government and promoted Hawai‘i’s 1839 Declaration of Rights and 1840 Constitution, which transitioned the island chain into a constitutional monarchy.

“Ka Lama not only enabled the world to creep in but hastened the speed by which America established itself in Hawai‘i,” she wrote. Hawai‘i businessmen also began printing English language papers in 1836 to promote their own economic and political ideas; they targeted foreigners living in the Islands.

But even as missionary editors pushed American values, ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i newspapers also helped decentralize and pass on Hawaiian knowledge by serving as central platforms for Native Hawaiian authors to contribute genealogies, mele, memoirs and biographies.

In Ka Nonanona, for example, historian Samuel M. Kamakau submitted the mo‘okū‘auhau, or genealogy, of Kamehameha III, which was debated by the traditionally trained genealogist A. Unauna. Noenoe Silva in a 2008 article in The Hawaiian Journal of History, wrote that this was the first of probably hundreds of debates in the papers over a variety of issues.

Silva is a political science professor at UH Mānoa. Her article identified nearly 310 authors in the first four ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i newspapers, all of which were controlled by missionaries: Ka Lama Hawaii (1834), Ke Kumu Hawaii (1834–1839), Ka Nonanona (1841– 1846), and Ka Elele Hawaii (1844–1855).

Another major debate took place in Ka Elele. In 1845, the paper published a petition signed by 1,600 citizens asking Kamehameha III to preserve the Kingdom’s independence and not allow foreigners to be appointed to high office. Kamehameha III and the legislature responded to that petition through the paper.

“Ka Nonanona and Ka Elele Hawaii became the primary Hawaiian language venues for public policy debates and struggles over whether the Hawaiian language, epistemologies, cultures and modes of governance were to remain hegemonic or be subordinated to English and the American ways,” Silva wrote. “Important arguments, narratives and discourses were printed in these pages that determined the outcomes of those struggles.”

Ka Elele’s July 15, 1845 issue. | Digital reproduction courtesy of Bishop Museum Library and Archives.

Larger Impact

The newspapers had an impact on ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i. Nogelmeier said they helped nationalize the language while maintaining and appreciating quirks and words that were only used in specific geographic areas.

They also showed that Kānaka Maoli actively worked to influence their world, Silva wrote. Native Hawaiians wrote into the papers in the hopes of having issues resolved and to let the constitutional monarchy know their opinions. Many authors were prominent officials, like David Malo, Ioane (John) Kaneiakama Papa ‘Ī’ī, and Deborah Kapule, Kaua‘i’s last queen.

“This helps us to understand that Kānaka Maoli were not passively colonized, nor was the process of putting new laws and government structures into place a simple one in which the ali‘i nui’s ideas remained stable or hegemonic,” she wrote.